The Roar of Legends: A Comprehensive History of the Isle of Man TT

The Ultimate Test of Man and Machine

Nestled in the Irish Sea, the Isle of Man is a small island with an outsized legacy in the world of motorsport. It is home to the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy (TT) Races, an annual event that stands alone as the most exhilarating, challenging, and, some would say, dangerous motorcycle race on Earth.

For over a century, the TT has captivated audiences and drawn riders from across the globe, all seeking to conquer the unforgiving Snaefell Mountain Course – a 37.73-mile circuit of public roads transformed into a high-speed arena. More than just a race, the Isle of Man TT is a crucible of courage, a testament to human limits, and a living museum of motorcycle engineering and evolution.

The Genesis: From Banning to the Birth of a Legend (Early 1900s - 1910)

The story of the Isle of Man TT begins not with a desire for breakneck speeds, but with a ban. In 1903, the Motor Car Act in the United Kingdom imposed a restrictive 20 mph speed limit on all automobiles, effectively outlawing road racing.

This legislative roadblock led Sir Julian Orde, Secretary of the Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland, to seek a more liberal jurisdiction. His gaze fell upon the Isle of Man, which, with its independent laws and enthusiastic local government, proved to be the perfect host.

Initially, car trials were held in 1904, but it was in 1907 that the first motorcycle race roared into life. On May 28th, the inaugural International Auto-Cycle Tourist Trophy was held on the shorter, 15-mile St. John’s Short Course. The event featured two classes – single-cylinder motorcycles averaging 90 mpg and twin-cylinder motorcycles averaging 75 mpg – emphasizing reliability and touring prowess, hence the “Tourist Trophy” moniker.

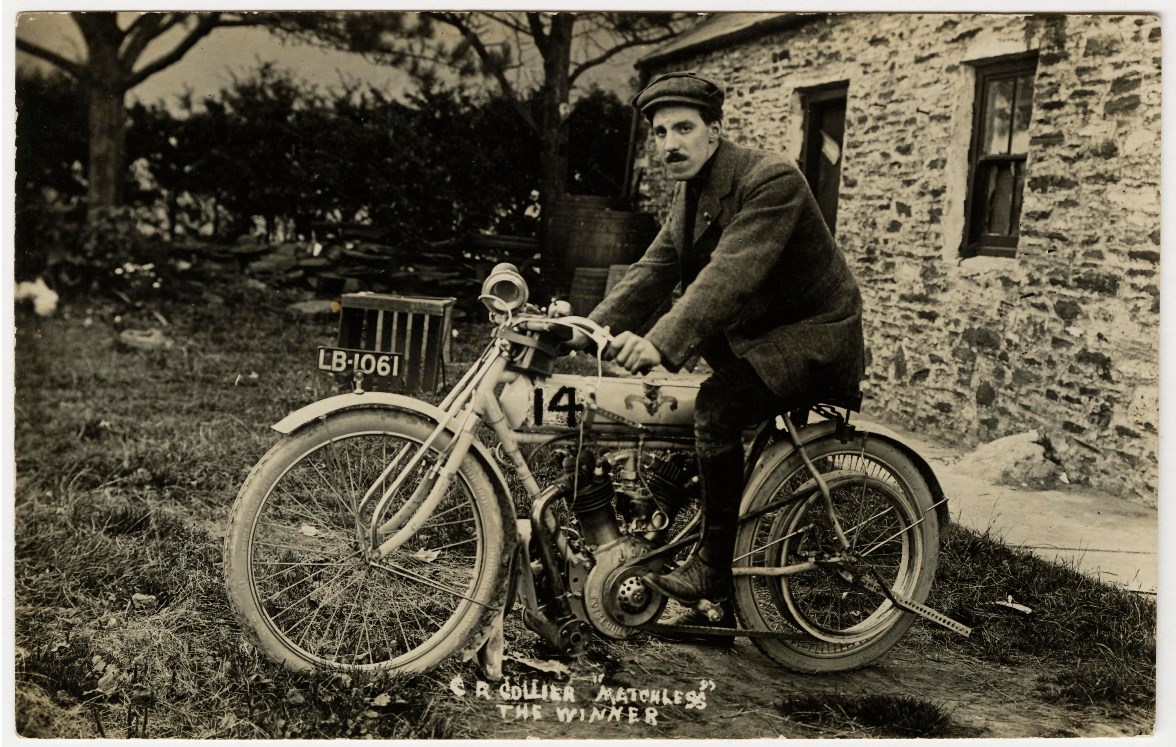

Charlie Collier, on a Matchless, won the single-cylinder race, while Rem Fowler claimed victory in the twin-cylinder class on a Norton. These early races were grueling tests of endurance, with few finishers among the brave pioneers.

The Mountain Course Era: A Legend Takes Shape (1911 - 1940s)

The year 1911 marked a pivotal moment in TT history with the introduction of the now-legendary Snaefell Mountain Course. This circuit, largely retaining its original layout, presented an entirely new level of challenge. Its twists, turns, elevation changes, and unforgiving stone walls transformed the race from a relatively sedate endurance trial into a high-speed spectacle. This move also saw the organization of the TT officially handed over to the Auto-Cycle Union (ACU).

As the years progressed, speeds increased, and the bikes evolved. Safety, while still rudimentary by modern standards, began to be considered; crash helmets became compulsory in 1914.

The races were, of course, interrupted by World War I (1915-1919), but they resumed in 1920 with renewed vigor and the extension of the Mountain Course to its current 37.73-mile length. The 1920s and 30s saw the emergence of true TT heroes. Stanley Woods, dubbed the “Irish Dasher,” made his debut in 1922 and went on to claim 10 TT victories, becoming one of the first multi-race legends.

Lap records were consistently shattered, with riders like Jimmy Simpson breaking the 60 mph barrier in 1924, 70 mph in 1926, and a remarkable 80 mph in 1932.

The TT also became a vital proving ground for manufacturers. Innovations in engine design, chassis technology, and tire development were relentlessly tested on the Mountain Course, pushing the boundaries of motorcycle performance.

The Post-War Boom and the Golden Age (1947 - 1970s)

Following another hiatus for World War II, the Isle of Man TT returned in 1947 and entered a new golden age. In 1949, the TT gained international prominence by becoming the British Grand Prix within the newly formed FIM Motorcycle World Championship. This era saw an explosion of technological advancement and the arrival of global stars.

Riders like Geoff Duke, with his smooth style and multiple wins in the 1950s, became household names. A monumental milestone was achieved in 1957 when Bob McIntyre recorded the first-ever 100 mph lap of the Mountain Course, a feat previously thought impossible. The 1960s ushered in an era dominated by legends such as Mike Hailwood, “Mike the Bike,” who notched up 14 TT victories, including an unprecedented three wins in a week in 1961.

Giacomo Agostini, another Grand Prix superstar, also made his mark, securing 10 TT wins and further elevating the event’s global prestige. This period was characterized by fierce rivalries, unparalleled talent, and a relentless pursuit of speed.

However, the increasing speeds and inherent dangers of the Mountain Course began to clash with evolving safety standards in Grand Prix racing. As circuits elsewhere became purpose-built and safer, the TT, with its public roads, faced growing criticism.

The World Championship Split and the Rise of Road Racing Specialists (1977 - 2000)

In 1977, a significant shift occurred: the Isle of Man TT was removed from the FIM Motorcycle World Championship calendar due to safety concerns. While a blow to its international Grand Prix status, this move inadvertently cemented the TT’s unique identity as the pinnacle of road racing. The event continued, albeit with a renewed focus on its distinctive challenges and the emergence of a new breed of rider – the road racing specialist.

The late 1970s and beyond belonged to one man: Joey Dunlop. “King of the Roads” and “Yer Maun,” the unassuming Northern Irishman became synonymous with the Isle of Man TT. His unmatched record of 26 TT victories, spanning from 1977 to 2000, across various classes, solidified his legendary status. Dunlop’s unparalleled skill, dedication, and humble demeanor endeared him to millions, making him arguably the greatest road racer of all time. His hat-trick of wins in 2000, at the age of 48, just weeks before his tragic death at a race in Estonia, remains one of the most poignant moments in motorsport history.

Other notable riders of this era included Phillip McCallen, Steve Hislop, and Carl Fogarty, all pushing the limits and etching their names into the TT’s folklore. Sidecar racing also continued to thrive, with legends like Dave Molyneux dominating their class.

The Modern Era: Pushing the Boundaries (2000 - Present)

The new millennium has seen the Isle of Man TT continue to evolve, embracing modern technology while retaining its raw, visceral appeal. Speeds have soared to unprecedented levels, with lap records regularly being shattered. Riders like John McGuinness, “the Morecambe Missile,” emerged as the leading force after Joey Dunlop, amassing an incredible 23 TT wins and earning his own “King of the Mountain” moniker.

More recently, Joey’s nephew, Michael Dunlop, has taken up the mantle, establishing himself as a formidable force with a fiercely aggressive riding style and now holding the all-time win record. Other contemporary heroes include Ian Hutchinson, Peter Hickman, and Dean Harrison, who consistently deliver breath taking performances.

Safety remains a paramount concern for the organizers, the ACU and the Isle of Man Department for Enterprise. Significant advancements have been made in track design, medical facilities, and rider safety gear. Air fences, improved run-off areas, and advanced marshaling systems are now standard. The 2025 TT, for example, saw an emphasis on predictive safety systems and the integration of IoT sensors and AI to anticipate dangerous conditions.

Despite these efforts, the inherent risks of racing on public roads mean that the TT remains a highly dangerous sport, with fatalities a tragic reality that underscores the immense bravery of the competitors.

The TT’s global reach has also expanded exponentially in the modern era. Extensive media coverage, including live broadcasts, documentaries, and online content, brings the drama and spectacle of the races to a worldwide audience, ensuring its continued popularity. The economic impact on the Isle of Man is substantial, with thousands of fans flocking to the island each year, boosting tourism and local businesses.

The Enduring Legacy: Why the TT Persists

The Isle of Man TT is more than just a motorcycle race; it is a cultural phenomenon. It is a profound blend of history, tradition, engineering prowess, and human endeavor. Its enduring appeal lies in several key factors:

- The Uniqueness of the Course: The Snaefell Mountain Course is unparalleled. Its sheer length, the diversity of its terrain, and the intimate proximity of spectators to the action create an atmosphere unlike any other sporting event.

- The Heroic Element: The risks involved elevate the achievements of the riders to almost mythical status. They are gladiators, facing down the Mountain with unmatched courage and skill.

- Technological Proving Ground: For over a century, the TT has served as a real-world laboratory for motorcycle manufacturers, pushing the boundaries of speed, reliability, and handling.

- Sense of Community: The TT fosters a unique bond between riders, teams, marshals, and fans. It’s a fortnight where an entire island embraces a shared passion.

- Tradition and Heritage: The event is steeped in history, with each year adding new chapters to a story that began over a century ago. The legends of the past are revered, and new ones are forged annually.

As the Isle of Man TT hurtles into its second century, it continues to defy expectations and captivate the imagination. It remains a powerful symbol of human courage, technological innovation, and the enduring allure of raw speed. The roar of the engines around the Mountain Course is not just a sound; it’s the heartbeat of a legend that will continue to resonate for generations to come.

Categories

- Bike Reviews (18)

- General Motorcycling (34)

- Rider Training & Advice (6)

- Roads & Rides (6)

- Why it Matters (5)

Recent Posts

About us

Popular Tags

Related posts

Merry Christmas & Happy New Year from the Team at Mallory Motorcycles!

Yamaha Y-AMT: The Automated Manual Transmission Set to Revolutionise UK Riding

Suzuki GB Launches New Off-Road Experience Centre: 300 Acres of Welsh Trail Riding Awaits

Nationwide Motorcycle Delivery

No corner of the UK is too far for the delivery team and it’s partners at Mallory Motorcycles. We proudly deliver to all major cities, towns, and even remote areas across the entire nation, including:

- London, England

- Birmingham, England

- Leeds, England

- Manchester, England

- Sheffield, England

- Milton Keynes, England

- Salford, England

- Sunderland, England

- Brighton & Hove, England

- Portsmouth, England

- York, England

- Colchester, England

- Chelmsford, England

- Exeter, England

- Gloucester, England

- Winchester, England

- Bradford, England

- Oxford, England

- Ripon, England

- Wells, England

- Liverpool, England

- Bristol, England

- Leicester, England

- Coventry, England

- Wakefield, England

- Nottingham, England

- Newcastle upon Tyne, England

- Doncaster, England

- Wolverhampton, England

- Kingston upon Hull, England

- Plymouth, England

- Derby, England

- Stoke-on-Trent, England

- Southampton, England

- Peterborough, England

- Southend-on-Sea, England

- Canterbury, England

- Preston, England

- Cambridge, England

- St. Albans, England

- Lancaster, England

- Norwich, England

- Chester, England

- Wrexham, England

- Durham, England

- Carlisle, England

- Worcester, England

- Lincoln, England

- Bath, England

- Hereford, England

- Salisbury, England

- Lichfield, England

- Chichester, England

- Newry, England

- Truro, England

- Ely, England

- Belfast, Northern Ireland

- Londonderry, Northern Ireland

- Lisburn, Northern Ireland

- Armagh, Northern Ireland

- Glasgow, Scotland

- Edinburgh, Scotland

- Aberdeen, Scotland

- Dundee, Scotland

- Dunfermline, Scotland

- Inverness, Scotland

- Stirling, Scotland

- Perth, Scotland

- Cardiff, Wales

- Swansea, Wales

- Newport, Wales

- Bangor, Wales

- St. Asaph, Wales

- St. Davids, Wales

Mallory Motorcycles Ltd is registered in England and Wales (Company Registration number 13948787). Registered Address Unit 2 Griffon Road, Derbyshire DE7 4RF. Authorised and Regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (number 1037062). Mallory Motorcycles Ltd is a credit broker and not a lender. We can introduce you to a limited number of finance lenders and for such introductions we will receive commission. The commission payment can be either a fixed fee or a fixed percentage of the amount you borrow. The lenders we work with could pay commission at different rates. The commission we receive will not affect the amount you repay under the credit agreement. All finance is subject to status. Terms and conditions apply. Applicants must be 18 years or over.